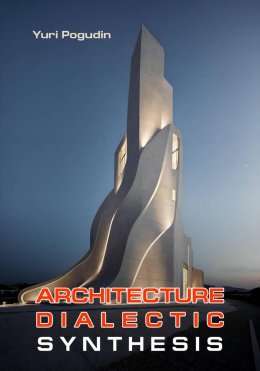

Читать онлайн Architecture. Dialectic. Synthesis

- Автор: Юрий Погудин

- Жанр: Архитектура, Педагогика

Dedicated to my family:

my wife Zoe and daughter Taya,

my mother Lyudmila, my father Alexander

and my sister Nina

Preface to the English edition

Dear readers, the translation of this book was performed by a friend of our family, Anna Kanunnikova. I am deeply grateful to her for the work.

The author hopes that the proposed direction will contribute to new architectural searches and discoveries.

September 14, 2025

Preface to the 2025 edition

Dear readers, in this edition, two interrelated works on the dialectical architectural concept are published together – "Dialectics of Architecture" (2006, Moscow: Litres, 2024) and "Synthesis of Architectural Form. From Meaning to Concept" (Moscow: Litres, 2023) – as well as "Manifesto…" (2023) and articles on the architectural and aesthetic theme (2024-2025), which are close to them.

In total, the works collected in this edition outline the dialectical foundations of understanding architecture and architectural morphogenesis on the basis of the philosophy and aesthetics of Aleksei Fyodorovich Losev (1893-1988) and the propaedeutics of the school of rationalism of Nikolai Alexandrovich Ladovsky (1881-1941). The author is aware of the controversial nature and the incompleteness of the work started. But at the same time, I agree with the statement by Aldo Rossi that architecture "is developing in many paths.1"

I hope that the book will not only be interesting theoretically, but also useful in the practical search for new forms and ways in modern architectural aesthetics.

I sincerely thank my family, the teachers who taught me, my mentors and my students!

Have a co-creative reading!

Feedback and comments can be sent to email: [email protected]

Yuri Pogudin. January 18, 2025

DIALECTIC OF ARCHITECTURE

Preface

The work offered to dear readers was created in 2001-2006 and became the general theoretical basis for the book "Synthesis of Architectural Form. From Meaning to Concept" (2023) that has an applied nature. After several years, the author perceives this first attempt to create a dialectical theory of architecture as successful and imperfect at the same time. But still, after minimal processing of the text written long ago, I have decided to publish it. For those who are already familiar with my publications on the topic of architectural morphogenesis (or architectural form generation), this work may be interesting as a kind of background, and as the development of general dialectical foundations of architecture. It will also be interesting to those who value the work of the great Russian dialectic philosopher Aleksei Fyodorovich Losev as an attempt to develop his ideas in the field of architectural theory.

The author expresses his wish that the "Dialectic of Architecture", forming a two–pronged work together with the "Synthesis of Architectural Form", inspire readers to develop and search for new ideas in incessant architectural creation.

Yuri Pogudin

October 14, 2023

Introduction

This work is devoted to understanding architecture, comprehending its philosophical and dialectical meaning.

The author has set himself two tasks: to formulate the essence of architecture and outline the foundations of its dialectical theory, as well as to consider architecture as a "philosophy in stone." These seemingly different tasks are combined in the idea that considers a person in the unity of spirit and body. Getting ahead of ourselves, let's notice that architecture from these positions is understood as an integral spiritual and material being unfolding in human nature, suggesting two points: 1. the continuation and development of the body in nature. From this point of view, architecture is understood as the second human body or the material side of his being presented in nature, and 2. the materialization of the worldview (theology, philosophy, creed, ideology, mythology). From this point of view, architecture is the embodiment of the ideal side of man in nature, ensuring the fullness of human existence in the world.

Essence of Architecture

Architecture as a Second Body

For a better understanding of the essence of the architectural form, let's compare it with the sculptural form. For this purpose, let us turn to the reasoning of Aleksei Losev in his "Dialectic of Artistic Form":

"…What is the difference between a sculptural form and an architectural one? To say that the difference lies in the material is ridiculous and strange. To say that one depicts people, and the other protects people from precipitation, is also ridiculous, because sculptures can have features protecting from precipitation, and architecture can depict a living being, something like the famous Trojan horse2. What is the difference, then? I see it only in the fact that architecture organizes pure materiality, that is, mass, volume and density, pure facticity and positedness, fixedness. There is nothing like that in the sculpture. Architecture gives weight to pure materiality, massive three-dimensional dense space, and presents space as a force field. That's why the architectural form is attributed to the first dialectical category in the general sphere of tectonism, to the category that speaks only of pure positing, pure potency, of the one, which as such is above all formalization, because it establishes and generates this formalization. Being reflected on the fourth principle, this principle gives, as we saw in paragraph 2, the categories of mass, volume and density. Architecture is the art of pure mass, pure volume and pure density, as well as their various designs and combinations. And the most important thing is that we thought of the fourth principle, as we remember, only as a carrier, a container of meaning, not meaningful in itself, but only positing, really fixing the intelligent element of pure meaning. Therefore, the architectural form is always the form of a carrier, a container of something else, more internal. An architectural work is architectural one not because it is a dwelling, a temple, and nature, but because its dialectical place is in the realm of pure hypostatization and positedness of meaning, from which it is clear why it is always a container. Sculpture, on the other hand, does not deal with space as such, that is, spreading as such. What is important to it is not the weight distribution itself in its qualitative nature, but what exactly is spread out, the single units that are spread out in a weighty way in space. If an architectural work is always a container, then in sculpture we already see what exactly is contained in the body, although not without the body, because otherwise it would be painting, poetry or music. Hence, in my classification, this form belongs to the category of incarnation of the second principle in the fourth one. The second principle, eidos, is precisely the semantic "what" of every incarnation in the sphere of tectonism. – Such is the dialectical structure of sculptural and architectural forms.3"

Architecture is a container, and the ability to contain is the main property of space. Space is primarily characterized by the ability to accommodate things, both at rest and moving. Therefore, architecture can be defined as a form of space, a material form of space. The sculptural form is the form of the material. Sculpture needs space as a sphere of its existence, while architecture is engaged in shaping this space. It explains the famous aphorism of Nikolai Ladovsky: "Space, not stone, is the material of architecture.4" Space is the subject of architectural activity, well-formed space is the goal of architecture, and materials and structures are the means to achieve this goal. Architecture obviously follows the path of liberation from materials and structures by striving to create structures that realize any form. Architect Leonid Pavlov spoke about this, crystallizing his thoughts in the paradox of the fundamental immateriality of architecture. Architecture, in the limit, strives to entirely free itself from the dictates of material and structures, and to become the architecture of certain force fields, etc. Of course, this means liberation from coarse material (metal, glass, concrete, etc.), and not from matter as such. The force field is also more subtle matter. And architecture always remains the material arrangement of a space containing people and nature. The means of architecture are evolving, but its meaning and purpose remain unchanged. In such a way, the form of the living space is created.

In the system of dialectics of the artistic form developed by Losev, architecture is 5quite logically attributed to the first semantic principle, since architecture is the most general unifying basis for all other arts. The basis is the first principle of Meaning in Losev's triad of Basis, Form, and Action6.

On the other hand, the dialectic of human activity derived from anthropology justifies the location of architecture precisely in the fourth semantic principle, since it is thought of precisely as embodying the Triune Meaning, as the body of Meaning7, and Losev quite rightly insists on physicality as the fundamental quality of architecture8. In addition, clarifying the brilliantly clear and simple Losev's definition of architecture as a container, it should be pointed out that architecture is precisely the container of the body, and, even more specifically, of the human body. Architecture reveals its meaning not just as a container, but as a container of the human body in its life and functioning. After all, a tree hollow accommodates a woodpecker, but it is not an architectural phenomenon. Further, as we understand essence of architecture in this way, it is necessary to establish a semantic connection between the building, the house as a unit of architecture and the human body. This connection is remarkably illustrated by Fr. Pavel Florensky. Developing the idea of so-called organoprojection, which is that "tools expand the scope of our activity and our senses by continuing our body," the 9philosopher writes: "Let us now turn to the synthetic tool that combines many tools and, fundamentally speaking, all tools. This tool is a dwelling, a house. All the tools are collected n the house, as the center, or are located at the house, near it, related to it, they serve it. What is the projection of a dwelling? What exactly is projected by it? By its design, the dwelling should combine the totality of our tools – our entire household. And if each tool separately is a reflection of some organ of our body from one side or the other, then the whole set of economy, as one organized whole, is a reflection of the whole set of functional organs, in their coordination. Consequently, the dwelling has the whole body in its entirety as its prototype. Here we recall the common comparison of the body with the house of the soul, with the dwelling of the mind. The body is likened to a dwelling, for the dwelling itself is a reflection of the body. <…> A house is like a body, and different parts of household equipment analogically correspond to body organs. The water supply system corresponds to the circulatory system, the electric wires of bells, telephones, etc. correspond to the nervous system, the furnace corresponds to the lungs, the chimney corresponds to the throat, etc., etc.10 And it is clear that it cannot be otherwise. After all, when we dwell in a house with the whole body, we accommodate ourselves in there with all our organs. Consequently, the satisfaction of each of the organs, that is, giving it the opportunity to act, occurs only through the house, and therefore the house must be a system of tools that extend all the organs.11"

It follows from the reasoning of Fr. Pavel Florensky that architecture is an organization and arrangement of the human economy in material structural shells. The economy is the unfolding of the body's functions in their entirety.

It is logical to extrapolate the meaning of the house as an extension of the entire human body to the entire architecture and think of it as the dwelling of humanity and the home of humanity's physicality. Architecture is, therefore, the continuation and unfolding of physicality in nature. This is the main essence of architecture in relation to the body category. Thus, in the dialectic of human activity, architecture correlates with the fourth principle of meaning, which is presented clearer in the table of concepts below.

Let us briefly summarize Losev's dialectic of man and his activities.

The category of architecture follows from the category of the human body, in relation to which nature is considered as otherness. Architecture arises as a result of placing the human physicality to other-worldly nature.

Hence, in order to clarify the dialectical basis of architecture, it is necessary to consider the place of the category of the body in the dialectic of man. According to A. Losev12, the dialectic of man is revealed in the following pentad:

1) Heart; 2) Mind; 3) Aspiration; 4) Body; 5) Person.

The body here acts as a substance that implements the triune elements of the heart, mind and aspiration. In the sphere of human activity, it will correspond to the triad of religion, science and art. Religion is the only element that captures the last depth of a person's being – the heart, and which calls for bringing this heart as a gift to the Absolute. Science results from the activity of the mind. Aspiration expresses itself in thirst and search for beauty, taking shape in art. In man, the heart, mind, and aspiration embody the body, and in human activity, religion, science, and art are embodied by architecture. This is also where Vitruvius' famous triad comes from – durability, usefulness, beauty, embodied in an architectural form. Thus, the following dialectical series arise:

The proposed system provides a solid basis for the widespread definition of architecture as a synthesis of science and art. Many books on architecture highlight the combination of scientific, technical and artistic principles in architecture as its distinctive feature. This means that architecture is neither a science nor an art, but a dialectical synthesis of both.

We will return to the triad of Vitruvius later, since now it is still necessary to highlight a number of significant points and historical explanations to the established basic understanding of architecture as human corporeality in nature.

So, architecture is not a second nature, but a second body, the second corporeality of humanity, it is the otherness of the human body in nature, its continuation and development, the unfolding of the body in nature. It results in the anthropomorphism of architecture as its main characteristic for many centuries.

Vitruvius refers to the human body as an example of artistic proportionality, arguing that "a beautiful building should be built "like a well-built man." Similarly, Michelangelo asserts that "the parts of an architectural whole are in the same ratio as the parts of the human body, and those who did not know and do not know the structure of the human body in the anatomical sense cannot understand this." He compares the exterior of the building with the face, which is primarily the exterior of the body. "If there are different parts in the plan," Michelangelo wrote, "then all similar parts in quality and quantity should be decorated and ornamented in the same way. If one part changes, then it is not only allowed, but also necessary to change its ornamentation, as well as of the respective parts. The main part is always free, like the nose, located in the middle of the face, it is not connected to either one or the other eye; the hand should be like the other one, and one eye should be like the other.13"

Architecture was developed based on the assimilation to the human body in Ancient Greece, as well as in Ancient Russia – and to an even greater extent, since not only individual parts of the temple (columns) are compared to the body here, but the temple as a whole. But even then, when architecture (the building as a whole, its parts) does not evoke associations with the forms of the human body, it is still, in its deep meaning, the mode of existence of human physicality in nature. It's about the meaning, not the external resemblance. Modern architecture, which has moved away from anthropomorphism, nevertheless cannot but unfold the body in nature. Externally, the architecture of a particular era may not only not express the similarity with parts of the human body, but also, on the contrary, show something superhuman and exceeding the immediate physicality. So, Egyptian architecture is distinguished by a certain grandiose power, with which a "little" man is incommensurable. But it was in Egypt that architecture had, like nowhere else, such a huge mythological significance – to realize and materialize human immortality through the preservation of the body. According to well-known Egyptian beliefs, only those whose bodies remained intact were awarded with the afterlife. The thick walls of the tombs and pyramids were a guarantee of eternal life: the trap system was an actual protection from robbers, from damage to the Pharaoh's body and memorial furnishings, and the durable stone both symbolized and materialized the idea of eternity.

Architecture as a Materialized Worldview

The developed understanding of architecture as second physicality is insufficient since the a man is irreducible to the body. Architecture fulfills the human desire for the fullness of being. After all, man is not only a body, but a conscious and self-conscious body, a spiritual being no less than a material one. As a thinking person, it is typical for a person to build a worldview, philosophy as a complete system of knowledge, beliefs and values. As a material being, man is characterized by the desire to realize and materialize his worldview and his philosophy, to translate it from the realm of meaning into the realm of being. Philosophy does not want to remain a pure mental construct, even if it is expressed on paper or in a painting, but it longs to be embodied, expressed in matter, materialized. Moreover, the worldview embodied and realized "in stone" turns out to be the shell, a kind of castle in which a person lives, and through the prism of which he perceives existence. In this regard, architecture turns out to be a model of the universe, a microcosm in which a person places himself not just as a place of protection from precipitation, but as a philosophical concept clothed in material forms and structures. And vice versa, philosophy can be viewed as the architecture of the mental world, and each philosophical concept can be viewed as a house in which its creator or admirer lives with his mind. Each piece of architecture can be considered as a worldview of the epoch expressed "in stone". The building of a great architect is similar to the philosophical work of an outstanding thinker. In connection with this mutual understanding of architecture in philosophy, and philosophy in architecture, Plato's thought is interesting. "When Plato builds his cosmology,– observes A. Losev, – he considers the material elements, together with their inherent design, as "building materials" for space (Tim. 69 a), which, obviously, is thought of here as a huge work of architectural art. Plato also tends to represent his Good, among other symbolic interpretations, in the form of a huge architectural work…"14. In their turn, on the basis of comparing the cosmos with an architectural work, some Christian saints showed the absurdity of atheism. So, St. John Chrysostom argues as follows: "There is no God. But if there is no foundation, how did the building appear? There is no creator of the house: how is the house built? There is no architect: who built the city?… There is no Creator: where does the world come from and how does it exist?" The same argument was formulated in an aphorism by D. S. Likhachev: "Consciousness precedes the materialization of ideas. God is a great Architect."

The importance of approaching architecture as a "worldview in stone" is confirmed by both ancient and modern architectural history. Architects of the twentieth century began their creative activity by putting forward concepts and manifestos, the ideas of which sometimes consciously and unconsciously turned out to be a resurrection of the old ideas of classical philosophers of Antiquity, the Middle Ages, and Modern times. So, functionalism was a kind of resurrection (albeit in a significantly distorted form) of Socrates' old idea of beauty as usefulness. L. Mies van der Rohe followed the principles of Descartes' rational method in his design15. This suggests that it is impossible to understand architecture without understanding its philosophical roots, and it is philosophical ideas that become the formative paradigms of architectural creativity.

This idea sounds even more vivid against the background of historical evidence of people's unwillingness to save on architecture. In ancient times, huge funds were allocated for architectural works, even if the state was not rich. Thus, the construction of magnificent pyramids and temples in Egypt, for which the pharaohs spared no expense, was one of the reasons for the depletion of the Egyptian state; Pericles devoted 80% of the state budget to the restoration of the Athenian Acropolis; in Rome, huge funds were spent on amphitheaters and the spectacles staged in them. "The stingy Vespasian built the world's greatest amphitheater… Except, perhaps, Tiberius, all the emperors, one might say, only competed in luxury, in splendor, in the size and variety of the spectacles they staged.… All these spectacles are a wonderful example of how it is impossible to explain any art form", including architectural one, in a vulgar economic way. 16 To this set of examples, we can add the phenomenon of skyscrapers, which, starting from 30-50 floors, are economically unprofitable17, which does not stop countries and companies from competing in physical highness.

Thus, the main role in explaining the architectural form is played by a person's worldview and world perception, and architecture can be defined as the materialization of a mentality. It should be noted that the materialization of ideology does not necessarily occur directly and im mediately as an implementation of the task set by the architect to express certain ideological principles, but it can be carried out indirectly. The "ideology in stone" can be fairly seen where, it would seem, everything is due to purely economic reasons. An illustrative example is the so-called "sleeping districts", serial houses that are built up on the outskirts of large Russian cities. On the one hand, their monotony is due to the haste in solving the housing problem caused by the influx of rural population into the cities. And at the same time, these "monotonous cells" express the Soviet ideology of "one comb" and the principle of "keep your head down."

Another common attempt to determine the architectural form is to explain it in terms of climatic conditions. The simplest definition of architecture says that it is a set of structures designed to protect humans from atmospheric phenomena. The need to take shelter in bad weather sometimes explains the very origin of architecture. Without denying the essential role of weather and climatic conditions in form generation, it should nevertheless be emphasized that it is not decisive either in the origin or in the development of architecture. Architecture would undoubtedly have arisen in such a hypothetical case if the climate and weather were favorable everywhere. After all, there are many buildings and structures (for example, religious ones), the appearance of which is in no way due to these factors. There is a well-known idea that if the Greeks had built a temple on Olympus, where it never rained, it would still have had a pediment. Rain causes only the sloping nature of the roof, but there are many specific options for sloping roofs. This means that when completing the temple with a roof with two symmetrical slopes, the Greek architect was guided not by meteorological knowledge, but by the principles of his worldview. The form-generating action of the architect becomes an act of expressing a worldview that is not constrained by either climatic conditions or economic opportunities.

Summarizing, it should be said that architecture is the material correlate of philosophy. Architecture and philosophy are correlative, like matter and idea. Just as philosophy performs an integrating function in the worldview sphere, architecture performs an integrating function in the sphere of material and bodily life. Just as philosophy synthesizes the knowledge of all sciences into one whole, architecture synthesizes different aspects of human bodily life in one indecomposable synthesis of items of determining positions of material works.

Let us conclude our discussion with a general definition of architecture: it is the construction, aesthetic and technical designing of the material structure of the natural space as a housing and economic environment.

The General Architectural Ennead

Function – Aesthetics

The understanding of architecture is usually based on the Vitruvian triad of strength – usefulness – beauty or, in other words, design – function – aesthetics (artistic iry, composition). Accordingly, constructive, functional and aesthetic aspects are identified in architecture in general and in individual buildings.

The most acute opposition in this triad is characteristic of the categories of function and aesthetics, which has found historical expression in the antithesis of classical ("old") and modern ("new", modernist) architecture. The latter is characterized as functionally conditioned, and the first one as saturated with various kinds of non-functional decorativeness. The term "minimalism" appears at one pole, and the concept of "architectural excesses" at the other.

The third part of the Vitruvian triad – strength or construction – eventually ceases to be a category defining the identity of architectural activity. Universal masters, engineers and artists in one person, such as Pier Luigi Nervi and Santiago Calatrava, continue to appear in architecture. But this does not change the general vector towards the gradual "dematerialization" of architecture. It is noteworthy that A. V. Ikonnikov named one of his books "Function, Form, Image in Architecture," thus leaving the topic of materials and structures out of the main discourse.

The understanding of architecture is based on the pair of "function-aesthetics". The structural system plays the role of a means to achieve functional and aesthetic goals.

Let's start our search for the dialectical foundations of architecture with the opposition "function-aesthetics". Opposites arise from the initial identity, and, having passed through the stage of confrontation, they unite in the separable integrity of synthesis. What are the opposite features of function and aesthetics?

A function in the most general sense is an activity. A function always implies that or who is functioning, acting. The function itself is used only in an abstract mathematical field. For architecture, functionality, including ergonomics, is primarily related to human physicality. It is precisely as a function of the body that the function is opposed to decor, decorations, etc., which do not give anything to direct physical comfort. But if we do not reduce the fullness of human nature to body alone, then we should talk not only about the function of the body, but also about the function of the soul and spirit, and, generalizing, about the function of man as a spiritual, mental and physical whole. If we understand the function in such a way, it becomes possible to overcome the antithesis of function and aesthetics. Aesthetics in this regard becomes a psychological and spiritual function18. The ideal side of a person is formed by the antithesis of mind and heart. According to the structure of a person, one can distinguish between the function of the mind, the function of the heart, the function of the will, etc. The function of the mind in its most general form is philosophy, since it is philosophy that is engaged in integrating all scientific, religious and other knowledge into one integral worldview. From this point of view, when an architect seeks to create a "theology in stone" in a temple, his actions are also functional, and temple architecture is spiritually functional. The functionalism of the twentieth century is the result of reducing architecture to purely materialistic understanding.

Aesthetics, which nourishes the human mind and heart, is perceived primarily visually. The tented roofs of ancient Russian churches serve as an illustration to the theological idea (striving for God) and a spatial landmark at the same time. This is just one example against a narrow understanding of the function. It is well-known that the space below the tented roof of the temples was completely unused and was isolated by the ceiling from the main part of the temple, where worship was held, as otherwise additional heating costs would have been required.

A function is the "what" of architecture, it is its content, what architecture expresses and formulates. Architecture is the architecture of the human function as a whole. Man in his functioning is the content of architecture and architectural creativity. Architecture, therefore, is the otherness not only of the body of a person, but of his entire nature, including his mind and worldview. Just as man himself is a synthesis of ideal and material principles, so architecture, which continues his being in nature, becomes a synthesis of the dwelling of the body and the dwelling of consciousness (ideology, mythology). And this is aesthetics that forms the second – ideal – plan, layer of architecture. Aesthetics is the architectural "how" of mythological eidos. Function and aesthetics are related as "what" and "how", or, according to the antithesis common to all art, as content and form.

Considering aesthetics from the point of view of function suggests the opposite. One of the examples of understanding function through aesthetics is given by the aphorism of F. Johnson: "The beauty lies in the way you move in space.19" Johnson obviously meant the movement of the body, but one can expand the concept of "movement in space" to the movement of the soul's feelings in the space of art, the movement of the mind in the space of philosophy.

Thus, aesthetics and function are dialectically interrelated. But this is not enough for dialectics, and having separately considered any categorical opposition, it seeks to synthesize it into a new integral category. For the antithesis of function-aesthetics, it is the architectural form itself that plays the part of such a synthesis.

It should be noted that a completely natural separation of function (in the sense of body function) and pure aesthetics is possible in special types of architectural creativity. There is a whole complex of structures that have no utilitarian purpose – such as monuments, triumphal arches, etc. They are completely dominated by the aesthetic principle. At the same time, there are whole types of architecture, such as industrial and fortifications, where function plays a crucial part.

Let's summarize the identified triad:

1) Functional and aesthetic original identity

2) The antithesis of function and aesthetics

3) Functional and aesthetic synthesis: architectural form

This triad reveals the dialectic of architectural eidos. Like any eidos, it strives to embody and become tangibly manifest, which transfers us into the sphere of architectural meon20.

Structure

The architectural eidos was based on the antithesis of function and aesthetics. Let us now find a meonal category embodying architectural eidos as an immobile substance.

The main quality of a substance is immutability. Immutability, considered from the point of view of pure change and pure temporal fluidity, is eternity. What is immutability, understood as eternity, in the sphere of architecture, which is meonal from the point of view of the first architectural and semantic triad? It can only be a very long stability in time, that is, durability. Durability is a correlate of immutability in the architectural field. If the substance is characterized by immutability, then the structure has (or should have) durability in architecture. Thus, structure is the substance presented architecturally.

What is a structure in itself?

In its most generalized form, a structure can be defined as a system of conjugations of material elements of an architectural form, realizing it as a material, substantial facticity. It is a way of the form existence in the world of dense matter.

Let us now define the structure through correlations with other areas.

Since the category of architecture is based on the category of the human body, let us find the bodily correlate of the structure. It's a skeleton. If the structure is the skeleton of a building, then the function is the totality of its systems and internal organs, and aesthetics is the living flesh of the i. As F. L. Wright wittily pointed out, Wright, "rattling bones is not architecture21." Cultivating a structure as an aesthetic value in itself is similar to the desire to express in speech not its meaning, but the grammatical rules of its construction.

From the general definition of the structure, let's move on to its detailing. Strength, stability, and rigidity are the main properties of a structure.

Strength is a function of a structure, consisting in its ability to maintain itself under various loads. This is the self-identity of the structure in relation to the moment when it began to experience the pressure of the load (or some other impact). If in the case of strength we are talking about the fundamental existence of the structure – its ability not to collapse under exposures and loads, then in the case of stability we mean the identity or constancy (equilibrium) of the spatial position of the structure under the same exposures and loads. Rigidity is characterized by the moment of immutability (or nuanced immutability) of the structure itself, without taking into account the general spatial position. Thus, it is possible to arrange the three known qualities of the structure into a sequential triad, where the same quality – constancy (otherwise identity, substance) in relation to loads and exposures – gives each time a new category depending on the type of semantic correlation:

1) The structure itself, as an actual reality: rigidity

2) The existence of the structure: strength

3) Spatial position of the structure: stability

Thus, a structure is the constancy of an architectural form in the world of actual substance, the realization of its substantial self-identity. A structure is the "how" of the material existence of the "what" of an architectural form.

Let's note that when understanding the form-structure relationship through the internal-external antithesis, these opposites flow into each other. In purely semantic terms, the form is, of course, "internal", that is, what is realized, and the structure is "external", what realizes. But in terms of material facticity, it turns out the opposite way: for the bodily sense of touch, the form is something external, the living flesh of the building, and the structure is its inner skeleton. Thus, during the transition from the ideal plan to the material one, the form becomes "external" from the "internal", and the structure, on the contrary, becomes "internal" from the "external".

Further development of the concept of structure involves the consideration of types of structures and is not included in the objectives of this work.

Layout – Tectonics

The structure is the first principle of the architectural meon. The second principle in architectural eidos is the antithesis of function and aesthetics. Now it is necessary to present a meonal modification of these categories from the point of view of the structure.

What is a function given in the architectural meon, in space and considered from the structural point of view? A function is a movement, a multi-component process that takes place in a building, to a building, through a building, and out of a building. Structural modification of a function means that it is taken as a system of spaces that organize the process of human activity. The system of spaces that defines the places of their isolation and overlapping is a layout. The layout is the formation of a function.

The layout should provide not only one particular function, but also be ready to flexibly respond to various life changes. The functional flexibility of the layout is one of the qualities that make the building vital and durable. The functional system of constructivism of the 1920s is characterized by invariance22, and I. Leonidov, contrary to the general trend of this movement, "sought to universalize the type of building – one spatial composition for a number of functions.23" Later, this trend was crystallized in the Seagram Building by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Among foreign architects, the flexibility of the layout also characterizes the works of K. Tange.

Further, let's modify the aesthetics category in a similar way. Aesthetics, given as a structure, is tectonics. Tectonics is not only an aesthetic interpretation of a structure, but also a structural expression of aesthetics. The demonstration of the structure's work has ideological and symbolic significance. Tectonics is the framework of mythological eidos given in the structure.

Let us briefly consider the types of tectonics. The main types of tectonics are the tectonics of material and the tectonics of space, according to the understanding of architectural form as a material and spatial synthesis. The tectonics of the material is antithetically divided into heaviness expression tectonics and heaviness overcoming tectonics.

When form and structure are identical (direct demonstration of the structure), it is called constructive tectonics. If the form and structure do not match (for example, the form envelops the structure without giving an idea of its work), it is called atectonics (for example, the Baroque style). When synthesizing form and structure, we speak about artistic tectonics: "a plastic form reflects the fundamental features of the structure.24"

Thus, the second architectural and meonal principle is formed by the antithesis of layout/tectonics. Layout is the tectonics of functional space, and tectonics is the structure of aesthetic space expressing myth.

The next step is a synthesis of tectonics and layout, correlated with the architectural form of the sphere of eidos. It is a building given as a fact or the fact of a building, that is, a building taken solely from the point of view of materiality, as a material that has become25.

Summarizing, the architectural meon looks like this:

1) Structure.

2) Layout – Tectonics.

3) The fact of the building.

The next logical area after the sphere of eidos and the sphere of meon is the sphere of synthesis of both, completing the overall architectural ennead. The synthetic domain, like others, contains its own identity, its own difference and its own synthesis, but the data are already as holistic as possible, as a synthesis of idea and matter. It all starts, as before, with the original identity of opposites, which we will call the architectural essence. The architectural essence is polarized into internal and external part, which are then synthesized in their unity. Let's move on to the specific dialectic of the external and internal in architecture.

Interior – Exterior

A building, as internal to itself and as external to itself, is, respectively, an interior and an exterior. The interior is the building in its internal expression, the interior of the building. The existence of the interior distinguishes an architectural form from sculptural and other forms. A sculptural form is a purely exterior form, it is external to itself. The interior contains the specifics of architecture as a container. The interior is the building's inward orientation, into itself as an integrity distinct from the environment. The exterior is, on the contrary, the building's exit outside, into the external world, its manifestation to the space of the surrounding world.

This only captures the antithesis of the interior and exterior as the opposition of the building to itself. Dialectics then examines categories from the point of view of their otherness, and establishes the transition of opposites into each other. Otherness to the building is a human subject. The interior is a form encompassing this subject. Consequently, the subject turns out to be an internal content in relation to the interior, and the interior in its relation to the subject is an external thing. The exterior category also undergoes a similar transition to its opposite when correlated with the otherness. The exterior in relation to the subject presupposes the possibility that the perception of the subject embraces it, if not simultaneously, then sequentially, with the in a circular, ambient motion. This means that the exterior is the inner content in the encompassing perception of the subject.

So, during the transition from the building-for-oneself to the building-for-the other and back, the external flows into the internal (and vice versa) within the framework of the interior-exterior antithesis.

There is another type of overflow of these categories – when moving from one to many in the category of architectural objects. This refers to a situation where many buildings, each of which is individually given externally, organize an interior urban space, provided that their layout is relatively closed. Such an example is a square. The same can be established regarding the direction from the interior to the exterior. If there is a number of rooms connected in a closed arc-shaped enfilade flow, then there is created the possibility of encompassing the perception of a part of the interior space, and this introduces an exterior moment in perception.

The next task of dialectics is to synthesize these categories. The synthesis of interior and exterior is the building considered as a whole. Leaving behind the discrete consideration of the building from the inside and from the outside and absorbing its integrity in a single semantic act, we are already returning to the original identity of the interior and exterior, but now with the preservation of the moment of their distinction. This synthesis, as a self-identical difference, is the building as a unity of container and shell, an integral architectural unity.

Let's combine the summary of the "interior-exterior" section with the previous results into a single categorical structure:

Architectural Ennead26

Architectural eidos:

a) Functional and aesthetic original identity

b) Function – Aesthetics

c) Architectural form

Architectural meon:

a) Structure

b) Layout – Tectonics

c) The fact of the building

Architectural integrity:

a) Architectural essence

b) Interior – Exterior

c) The building as a unity of container and shell

The proposed ennead summarizes the most basic architectural categories. Further movement along the planned path leads us to more specific architectural concepts such as scale, wall, window, etc. We will consider them not only from an abstract logical point of view, but also from a specific mythological one.

Scale Category

The first chapter dealt with the embodiment of human consciousness in architectural matter. This process is accompanied by the reverse process: once erected, the building begins to live in the physical space and in the space of human perception. The architectural object is embodied (in other words, it affects) In human consciousness, primarily in the most general category – size or magnitude. In human perception, this category is modified into a scale system. The size of the building either dominates consciousness (mega-scale), or is relatively small (micro-scale), or, finally, is commensurate.

Next, it is necessary to give a clarifying modification of the scale category in connection with the human body. A person perceives the dimensions of a building not only as an object "in itself", but in relation to the size of his body. According to the previous division, the buiding can be commensurate with the human body, and therefore psychologically comfortable. If the building is disproportionate, they speak of the "indefiniteness of the physical dimensions of the structure.27" This method of realizing size in perception was used by ancient Egyptian architects, creating colossal undifferentiated arrays of pyramids. The masters of the Western European Middle Ages, on the contrary, introduced many divisions into the flying vastness of space. It is no coincidence that O. Mandelstam in his poem connected Gothic with "Egyptian power": Egyptian structures are the power of the material expressing heaviness, and Gothic buildings are the power of space, overcoming this heaviness.

Summarizing the above in relation to the architect's work, we can say that the essence of the scale system is that by adjusting the degree of fragmentation of the volume, it is possible to control manifestations of its size in human perception, that is, to increase, decrease or reveal equivalently to the real physical size. The architect chooses one way or another to synthesize the size of a building and its perception by a person, depending on the nature of the mythological eidos he embodies. Here are some more examples from classics and modern times. We find many variants of "direct correspondence of proportional scale characteristics of architecture to the size of the human body in the ancient experience… <…> However, the ancient Greeks, and after them the Romans, creating spaces for human habitation and activity adapted to man and commensurate with him, never forgot that the house of god – a temple – must have different qualities and a different scale than a human dwelling, so that a person entering a temple feels that he is not going to his own house, but to the house of god.28"

In modern architectural practice, there are examples of other applications of the scale system, related not to mythological attitudes, but to the development of architectural science as such. Thus, one of the main provisions of Soviet rationalism, put forward by N. Ladovsky, was "saving mental energy in the perception of spatial and functional properties of a structure.29" According to this thesis, the architect should make every effort to ensure that the geometric characteristics of the building are read as adequately as possible. The opposite approach is observed, for example, in the works of the Finnish architect Reima Pietilä, who does not open the entire structure and suddenly amazes those who enter with the vastness of the interior spaces.

Let's also note that the relativity of scale system consists in its dependence on the age of the perceiving person, on his height, as well as on the specific features of the process of visual perception of forms and spaces30.

The Dialectic of Function

The basic functional typology of buildings and premises is derived by us on the basis of the triune hierarchical structure of human nature. In accordance with the triad of spirit, soul and body, we will distinguish:

1)

the architecture of the spirit

(sacred, temple architecture)

2)

architecture of the soul

(museums, theaters, universities, libraries, cultural and community centers, etc.)

3)

the architecture of the body

(restaurants, hotels, industrial buildings and structures, etc.)

Further, the same triple division can be carried out in the interior system inside a residential building. After all, a residential building is a type of building that accommodates almost all human functions. The design and realization of bodily needs include rooms such as a kitchen, dining room, bedroom, bathroom, etc. Hierarchically higher are rooms such as the living room, study, workshop, related to the mental organs and their functions (communication, cognition, creativity, etc.). Even higher is the area of the spirit, the room where a person realizes his religious faith, for example, the room where he prays. Inside a palace or university, it is a temple that is a part of it. Inside a separate room in a Russian hut, there was traditionally a "red corner" with icons. It was in this corner that K. Malevich hung his symbolic black square, which thereby proclaimed the formation of a black hole in the human soul, expelling God from his life.

Thus, the first functional antithesis arises – sacred, consecrated and ordinary premises both in the general structure of the building and as a special type of buildings. Juri Lotman writes about this as follows: "The house (residential) and the temple oppose each other in a certain respect as profane to sacred. Their juxtaposition is obvious from the point of view of cultural function and does not require further reasoning. It is more important to note the common feature: the semiotic function of each of them is gradual and increases as it approaches the place of its highest manifestation (the semiotic center). Thus, sanctity increases as one moves from the entrance to the altar. Accordingly, the persons admitted to a particular space and the actions performed there are positioned gradually. The same gradation is characteristic of residential premises. Names such as "red" and "black corner" in a peasant hut or "black staircase" in an apartment building of the 18th and 19th centuries clearly indicate this. The function of a dwelling is not sanctity, but security, although these two functions can overlap: the temple becomes a refuge, a place where protection is sought, and a "holy space" is devoted in the house (hearth, red corner, the role of the threshold, walls protecting from dark forces etc.)31.

We have identified the antithesis of ideal (spiritual and mental) and material (bodily) functions. Is their synthesis possible?

If the concept of a material function includes the function of protection from the enemy (fortification), then one of the clearest examples of synthesis is the Athenian Acropolis. The acropolis, a fortified part of an ancient Greek city, by definition, performs a twofold function – it contains temples of the deities under whose protection the city is located, and serves as a shelter for the townspeople during attacks32.

Another example of synthesis is a medieval monastery. This is a place of residence for monks, a defensive fortress, and a crossroads of trade routes, the goal of pilgrims, not to mention the self-evident main function of promoting the salvation of the soul.

According to the functions of communication (socially given identity), privacy (socially given difference) and their complex conjugation, one distinguishes between communication spaces (living room, kitchen, etc.), privacy spaces (study, bedroom, etc.), and mixed types of spaces. It should be noted that the oppositions of ideal – material functions and communication—privacy functions are not correlative and therefore overlap each other in the system of living spaces. Thus, the study and the bedroom, which are opposite in the first of these antitheses, are identical in the second function (privacy).

The next, equally important antithesis of the functional sphere is the opposite of living space, recreation space and work space. In megacities, this antithesis causes discomfort to many people from the spatial separation of "sleeping areas" and institutions, enterprises, offices clustered in the central part of the city.

The synthesis of dwelling and work functions at the level of individual houses is interesting. Here again, we recall the tradition that lived in the Middle Ages as well of placing living quarters and work premises (on the ground floor) in the same building. There are examples of such a synthesis in modern architecture. Thus, a complex of villas has been built in Berlin, each of which "performs, in addition to the residential function, the tasks of an infrastructure element. This is achieved by the fact that each villa is inhabited by an entrepreneur whose company is engaged in public service and it is located in the same house <…>. Such an unusual for modern urban planning method of performing "social, cultural and residential function" essentially revives the traditions that were forgotten today, when a merchant lived above his shop… Combining dwelling and a place of work in one building acts on the one hand as an effective method of saving urban land, and on the other hand allows you to erect significant construction volumes that carry a representative essence, important for the owner and ensuring the urban significance of the building.33"

There are two more important antitheses inside a separate building:

1) The main premises are service, connecting premises (communications – elevators, stairs, corridors, etc.). The synthesis between them takes place at the aesthetic level, when communications are not hidden in the thickness of the building, but are brought out, participating in the creation of the artistic i of the building and giving the opportunity to feel its inner life from the outside34.

The project of the new city by architect A. Sant’Elia in 1914, brought this principle to its ultimate state: the basis of spatial composition is determined by the communication system. Examples of a "moderate" synthesis are the theater building in Rostov-on-Don (architects: V. Shchuko and V. Gelfreich, 1930-1936), the Gosprom (Derzhprom) building in Kharkiv (S. Serafimov, M. Felger, S. Kravets, 1925-1928).

2) Servant vs. served spaces. This antithesis was of particular importance in the work of L. Kahn. The American architect developed the thesis about the separation of these types of rooms. "Working on a small facility, a swimming pool, led me to the theory that the servant spaces and the servant ones should be separated. This distinction has become the basis of all my plans.35"

The opposite approach to the solution of the internal functional space is presented in the concept of another famous American architect, F. L. Wright. He put forward the thesis of "the unity of the internal space.36"

From a dialectical point of view, an approach is possible that does not place a separate em on either the unity or the separateness of the building spaces, but follows the principle of single separable integrity. In addition to pure dialectics, such a teaching has deep foundations in the modern understanding of the physical structure of space. Space is created by light, which is characterized by wave-particle "wave-particle "duality" (one can say "synthetism"). Depending on the specific circumstances, light behaves either as a particle or as a wave. The physical world turns out to be a school of dialectics. After all, a particle is nothing but a materially given identity (as a point is the identity of the beginning and the end), while a wave is a difference in the quality of extension (as a line is the difference of the beginning and the end). Thus, physical space is a single separable whole. This is an additional basis for formulating a similar doctrine in relation to the functional space of architecture.

Let's list the main antitheses of the architectural and functional environment:

1) sacred – ordinary;

2) communication spaces – privacy spaces;

3) working and residential spaces;

4) connected – connecting rooms (communications).

5) served (main) – servant (subordinate).

These antitheses reveal the dialectic of function in general terms. So far, we have considered architecture primarily as one or another organization of space. But space is inseparable from time and from history. Taken from the point of view of temporal formation, architecture reveals to us the whole complexity of the historical relationship between the old and the new, the past and the future. The second part of the work is devoted to the historical formation of the architectural form.

The Antithesis of Historical Space and Architectural Form

The antithesis of the new and the old, from the point of view of architectural history, is the antithesis of traditional and innovative architecture, classical and modern, avant-garde one. Classical architecture itself contains this juxtaposition of antiquity and the Middle Ages. The frame system of the Gothic cathedral is something radically new in comparison with the rack-and-beam system of the Greeks. "Classics" and "avant-garde" permeate the entire history of architecture.

In architectural creativity, this antithesis in its untamed form has given rise to two opposing approaches to design. In Soviet architecture, I. Zholtovsky was a prominent advocate of the growth of new forms based entirely on the experience of past architecture. Such architects as K. Melnikov, I. Leonidov stood for principal innovation. So, "Leonidov had a strongly negative attitude towards architects, for whom the creative process is the use and processing of some forms and details that have already been created by other architects. He did not even recognize them as genuine architects, because, in his opinion, they do not understand the meaning of the architect's work, they make architecture purely externally, and not from the inside, which is not real creativity. They take something ready-made and put things together from it. Leonidov considered I. Zholtovsky to be an architect of this type, therefore, he was highly critical of his talent and creative style. Leonidov was convinced that beauty cannot be composed of elements of ready-made beauty, but must be created anew. In this, he really radically disagreed with the creative concept of Zholtovsky, who saw in the legacy (that is, in the works created by others) an inexhaustible source of compositional ideas, forms and details.37"

Already in our time, Frank Gehry spoke vividly about the role of the past: "You can learn from the past, but not continue to be in the past. I can't look my children in the eye if I say I don't have any more ideas and have to copy the past. It's like giving up and saying they don't have a future anymore.38"

In order to keep in touch with the past and at the same time make a move into the future, in order to ensure the historical comprehensiveness and full value of the architectural form, it is necessary to combine both approaches in design. An example of such a synthesis is the work of St. Petersburg architect Igor Yavein. "A thoroughly erudite man, Yavein knew well and studied the history of world architecture throughout his life <…>. But when he started designing, he didn't use special literature: he kind of started everything from scratch, without any prototypes or sources.39"

The history of architecture knows attempts to synthesize the "old" and the "new" at the level of entire trends. One of them is "a unique and little-studied movement of the 1920s and 1930s – Art Deco. It was a phenomenon of architecture of the "integrating type". Based on the innovations of the pioneers of new architecture, Art Deco did not break with history." But "it was, to a certain extent, a continuation of eclecticism," 40according to Yu. I. Kurbatov, and therefore did not last long. Any eclectic combination is short-lived due to the external nature of the conjugation of different forms. Dialectics directs us towards combining the very principles of classical and avant-garde form creation into new synthetic principles.

It should be noted that "an analysis of the means and techniques of artistic expression of the new architecture shows that much of them not only has a continuity with the past, but also does not go beyond the established stereotypes.41" This suggests that despite the visual gap between the old and the new architectures, they have a lot in common at deeper levels, which gives additional reason to assert the possibility of their synthesis.

The concept of history is not identical to the concept of continuity. History is broader than continuity. History is an interweaving of evolutionism and leaps. In the sphere of historical space, we discover the same dialectic of continuity and discontinuity as in the field of physical and architectural spaces.

Examples of historical combinations in modern architecture are new buildings next to old ones. Due to their spatial proximity, these different structures effectively emphasize each other's uniqueness by contrast. "The true effect lies in the sharp opposition; beauty is never so bright and visible as in the contrast" 42(N. V. Gogol).

A striking example of the synthesis of traditional and new architecture is the work of the Japanese architect K. Tange. Le Corbusier's student transformed old Japanese traditions into ultra-new architectural solutions.

Essays on the History of Architecture by Antithesis

In this section, presented as experimental historical essays, the author suggests looking at the history of architecture from the separate perspectives, each of which is set by a specific and irreducible architectural opposition.

Cubicity – Sphericity / Straightness – Curvilinearity

Sphericity relates to cubicity in the same way that identity relates to difference. Sphericity is the state of a form when all its parts are so identical that it is no longer possible to distinguish any parts on the surface of the form. From the absence of parts, it follows that a spherical form is a pure identity that has no internal boundaries. The ball is infinite for an ant crawling on it, although it is finite for the person holding it in his hand.

The geometrically modified boundary category is an edge. An edge is what divides a form into distinct parts and makes it differentiated. A form containing edges, and therefore faces, is a difference from the point of view of eidos. It's a cubic form.

Thus, a spherical form is a single surface in which we cannot distinguish parts (faces), since we have no edges (borders). The cubic form is quite clearly composed of several clearly distinguishable surfaces.

The synthesis of sphericity and cubicity (facetedness) is a form containing both sphericity and cubicity. This form, on the one hand, is spherical, streamlined, and has no edges, and on the other hand, it is divided into distinct faces. Dialectics strives to preserve the subject as a whole and therefore insistently reminds that any sides, aspects, predicates, etc. of any subject are both identical and different at the same time. An object is a synthesis of its sides, properties, etc. in one indecomposable unity.

The limiting expressions of sphericity and cubicity in the geometric domain are, respectively, a ball and a cube. The ball is a pure identity, since it has the same curvature at all its points, and is completely identical to itself in any spatial position, absolutely symmetrical with respect to any axis passing through its center. The cube perfectly expresses the principle of facetedness, since all its adjacent faces are perpendicular. Perpendicularity is the ultimate degree of difference between two or more straight lines and planes. Any other angle between straight lines or planes will be their convergence, which tends to complete coincidence of the elements (at an angle of 0 or 180 degrees).

Let's give examples of cube and sphere synthesis:

1) a cube made up of balls or a ball made up of cubes

2) a straight cylinder with a height equal to the diameter of the base (one of its orthogonal projections coincides with the projection of a ball (circle), and the other with the projection of a cube (square)

3) the eighth part of the ball is the most complete synthesis (from the one side, an exact cube, and from the other, an exact ball)

4) all the countless complex stereometric forms with rectilinear and curved surfaces

The antithesis of sphericity and cubicity becomes especially intense when we take it in its mythological aspect. Sphericity is a property directly visually and mythologically attributed to the sky, as evidenced by such a stable expression as "celestial dome". Both the physical and spiritual sky possess the property of "globularity". "… The world of bodiless powers, or the Heaven, is a sphere that has a straight line around it <…> We look at the Heaven so that the Sun is between it and us. Therefore, we look at the Heaven from God's side. It is quite understandable that it appears to us as an overturned Chalice. The Heaven is a Chalice not because it seems so to our subjective gaze, but it seems so to us because the Heaven, in its inner and most objective essence, is nothing but a Chalice.43"

If the heaven is a chalice, then what is the earth? According to the principle of a simple opposition, the earth is a cube. According to A. F. Losev, the ancient Greek thinkers associated the element of the earth exactly with the cube44. The body is an earthly, earthy principle in man (Adam was created from the earth), and therefore "the whole body, made up of individual members, is square.45" The body is square not in appearance, but in the sense of its relation to the spirit, expressed geometrically.

Thus, within the spherical nature itself, we find both sphericity (heaven) and cubicity (earth). According to this division, the antithesis of top and bottom appears in the building: the roof, which interacts with the sky, and the foundation with the walls, which determine the interaction with the earth. It is easy to notice that most roofs and ceilings in the "old" architecture of different styles and eras are often spherical (domes, arches, cones, etc.). Both the Pantheon and St. Sophia of Constantinople are covered by a spherical form. The lower part of buildings, on the contrary, is solved as faceted, cubic. This correspondence of the bottom of the building to the cubic form, and the top to the spherical form, is probably partly due to the round shape of the human head – the upper part of his body. In ancient Russian architecture, there was a direct associative correlation: the dome is the helmet of a warrior hero.

The antithesis of "ball-cube" has a deep philosophical significance. It geometrically expresses the semantic opposites "nature-technology", "heaven-earth", "spirit-body".

In this regard, it is possible to suggest a classification of architectural structures. An orthogonally parallel structural system – a rack-and-beam one – corresponds to the cube. Arched, vaulted, shell-shaped structural systems correspond to the ball.

The struggle between the cubic and the spherical permeates the history of architecture. In the history of classical architecture, these trends were most obviously crystallized in the rationality of Classicism and the emotionality of the Baroque, which became a ramification of Renaissance synthetism. An example of the synthesis of these styles is the Palace Square in St. Petersburg.

In modern architecture, this struggle is even more acute, on the basis of which A. V. Ikonnikov argued that "it was only in the architecture of the twentieth century that trends emerged that focused on one of the polarities that had always previously acted inseparably.46"

The cubic form is often correlated with the technical one, and the spherical form with the natural, bionic one, although this correlation is optional. The architecture of Antonio Gaudi may serve as an example of the second case. One of his most famous works, the Casa Milà in Barcelona (1902-1910), is characterized by its "naturalness", smoothness of lines, curves, and fluidity of form. This is an example of Art Nouveau architecture, tending towards natural, curved outlines.

In German architecture of the 1920s, the "struggle between cube and ball" was expressed in the confrontation between neoplasticism (Theo van Doesburg, Piet Mondriaan, Gerrit Rietveld) and expressionism (Erich Mendelsohn, Hans Poelzig)47.

This antithesis can also be traced in Soviet architecture – in the difference between the design methods of constructivists and rationalists. "Constructivist buildings also reflect orthogonal drawings in their style, and there is little plasticity in them. The works of rationalists are more plastic, often there are no facades at all that could be drafted in orthogonal drawings.48"

Ivan Leonidov is a non-typical constructivist. "Back in the late 20s and early 30s, Leonidov used forms with a second-order generating curve, shell vaults in his projects along with rectangular prismatic volumes…"49.

Expressionism has become a relatively synthetic trend in modern architecture, one of the representatives of which is E. Mendelsohn. "Unlike the orthogonal, monochrome solutions of the modernists, Mendelsohn uses the contrast of orthogonal forms with curved ones.50"

In the history of architecture of the twenty-first century as a whole, there is a strong bias towards complicated curved forms, accompanied by criticism of modernism51.

Let's move on to the next point of the architectural form – let's consider it not only by itself, but also in relation to the otherness of space.

Massiveness – Transparency / Closeness – Openness

The dialectic of form as such, in itself, is outlined by the antithesis "sphericity – cubicity". The next point of logically consistent thinking of a form should be its correlation with space, and this correlation is when we are also interested in the form itself. This point is revealed by the antithesis "massiveness – transparency".

And here we find three fundamental relations of form and space – their identity, their difference, and, finally, synthesis.

What is the identity of form and space? This means that space and form communicate and mutually penetrate each other completely unhindered. Space encompasses the form and enters into it, and the form stays in space and encompasses it. This is possible only if the form is thought of as loose and unsaturated, absolutely transparent and permeable. But this means that the form is represented only by its outlines, borders, and edges. It is a form built exclusively of edges, filled with nothing but space, elaborate and open to external and internal penetrations.

Even earlier than N. Ladovsky, who said his famous aphorism52, the sage Lao Tzu emphasized that the importance of a building is in the space for life and filling it. Space was the dominant element of ancient Japanese and Chinese architecture, as N. Brunov writes in detail53. Thus, the Japanese and Chinese pavilion houses organize a gradual transition from the mass of the building to the space of nature, as opposed to the sharp contrast of surroundings and architecture originating from Renaissance palaces.

In modern architecture, the fusion of form and space is achieved by means of form perforation and the widespread use of glass. Transparent glass is the only material that allows spaces and objects to be considered identical while maintaining minimal differences. Glass with mirror properties already visually prevents the environment from entering from the outside, but allows houses to dissolve into each other. The environment loses its clear boundaries, and its i is doubled and repeated tenfold by multiple reflections. Such interpenetration and mutual dissolution of objects in each other creates the illusion of overcoming the gravity and immobility of matter. It is a shimmering, pulsating medium where shapes blend and color each other.

The second type of relationship between form and space is a difference. Taken to its utmost extent, it will give a form that is fenced off from the outside space, self-contained, closed, and possibly opposing itself to the environment. Here, first of all, one remembers the thicknesses of the Egyptian pyramids and the walls of Romanesque castles. It's a massive form.

Finally, a synthetic way of relating form and space will be a form that is both massive and elaborate at the same time. It is both open to space and has isolated areas within it. In the history of architecture, there are examples of such solutions that have demonstrated the power of the combination of opposites.

The antithesis of "massiveness – transparency" correlates with the antithesis of relationship with the landscape. The openness of the form can mean a connection not only with an empty space, but also with a space filled with natural forms.

Let's recall the Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut in Deir el-Bahari. The powerful dynamic ramps of the building are energetically turning into ledges of natural rocks. The temple is clearly distinguished from its surroundings by the measured rhythm of the pillars of the porticos, and at the same time merged with it – to the point of literally cutting into the rock.

An example of the new architecture is the Sainsbury Center in Norwich designed by N. Foster (1977). Among other advantages of the project, one is interesting for our topic: "from the sidewalls, one can look through the huge building, as though merging with nature. From other points of view, the laconic outline opposes it. The huge portals of the ends of this supershed, framed by trusses, are literally open to nature. They serve as a kind of frame, the backdrop of beautiful landscape paintings, and the external space rushes through the giant structure with a roar, imparting unexpected dynamism to its statics."54

Jean Nouvel demonstrated unexpected identifications and syntheses of the massive and transparent, architectural and natural in a number of his works. In the Soho Hotel in New York's Broadway (2003), "transparent, semi- and not at all transparent give rise to "transit effects", the transition of one into another, as a result, the building seems massive or permeable depending on the time of day, the weather … – the impression of instant dematerialization, the appearance and disappearance of matter.

A more sophisticated stage is the dissolution into the landscape, nature… The Museum of Ancient Cultures on the Quai Branly in Paris (2001) is fused with an exotic natural environment, you forget about its man-made nature… At the Guggenheim Museum in Tokyo (2001), architecture in general seems to be absorbed by nature – a hill in flowering trees, and the exhibition spaces inside, stained glass windows are masked in the folds of the relief… The seemingly fantastic formula has been realized: the invisible architecture turns out to be the most impressive.55"

The two antitheses of developed by us, sphericity vs. cubicity and massiveness vs. transparency, mutually intersect in a broader antithesis of architectural form versus natural form. The history of architecture has witnessed two opposing trends. One tries to connect architecture with landscape. The synthesis model was developed by the same Japanese and Chinese architecture, which organizes a complex spatial proportion: the main room of the building correlates with the surrounding bypass connecting it to the outside space, just as the whole building correlates with the garden connecting the house and nature. Both the architecture and the garden are dominated by a curved line.

The opposite concept to this approach is the contrast of form and environment. It was followed, for example, by Ivan Leonidov, who believed that the new city (Magnitogorsk) should cut into a green massif, contrasting with the surrounding nature by the geometricity of its layout and the rhythmic row of glass crystals of multi-storey residential buildings dominating other buildings forming a rationally organized network of servicing institutions56.

Architecture in this concept is opposed to nature as something rational and orderly to irrational and chaotic. In this contrast, a side of the essence of architecture is expressed. Man strives to overcome the chaos of natural forces, to crystallize and strengthen a certain stronghold in the sea of circulation and spreading of natural phenomena. "The city becomes an i of … a world completely created by man, a world more rational than the natural one… The rational is thought of as "anti-natural."57 The i of St. Petersburg is illustrative in this regard. "If we take old Petersburg, then the cultural i of the military capital city, the utopian city, which is supposed to demonstrate the power of the state mind and its victory over the elemental forces of nature, will be expressed in the myth of stone and water, firmament and mud (water, swamp), will and resistance.58" This understanding of architecture was very characteristic of the Renaissance and utopias.

Architecture is the design of oneself, one's own physicality, and the surrounding space. Architecture is the self-organization of society, it is the desire to get used to the natural world, make it your own, organize yourself in it and organize it according to yourself.

The moment of confrontation with nature is also associated with another one, the opposite, which consists not in conquering, but in the peaceful development of nature. The task of architecture, Hegel argues, as a "symbolic" art, is "to work out the external inorganic nature in such a way that it becomes related to the spirit as an artistically appropriate external world.59" The task of architecture is to overcome the conflict between nature and man, making nature related to man and man related to nature, and removing the opposition between them. The purpose of architecture is to make nature dear, kindred, close, instead of hostile and threatening, to humanize it.

Meter – Rhythm / Regularity – Randomness

First of all, let's notice the connection between the categories of rhythm and meter with the previous antithesis. The meter is a symmetry expanded into a spatial series, and the rhythm is an expanded ordered asymmetry. From this we can immediately conclude that rhythm and meter are opposites, like movement and rest.

What are rhythm and meter?